Against Transparency

The idea of total transparency in society clashes with the most virtuous meaning of the word trust

Hamilton dos Santos

This article was originally published at Global Citizen Project, presented by Valor Econômico and Santander, in november 2019.

“Go, go, go, said the bird: human kind Cannot bear very much reality”

T.S. Eliot (Burnt Norton, Four Quartets).

A striking feature of the early decades of the 21st century was an obsessive need for transparency. In the beginning of this century, a bestseller by Dan Tapscott and David Ticoll titled The Naked Corporation (2003) stated that transparency would ultimately revolutionize all aspects of the economy and markets. They claimed that companies and organizations should begin to rethink their core values. Furthermore, they believed that all of us, men and women, should be prepared to be naked 24 hours a day. Of course, the phrase “being naked” the authors used is an ethical metaphor rather than a physical one. In fact, it was certainly a shrewd metaphor: if we are to be naked, they suggested, then it is better to be fit.

Although the idea of transparency, put forth in the book, was recognized more in the business world it was slowly gaining traction in all fields, especially in the realm of international politics. Vinicius Mariano de Carvalho, a researcher for Brazilian studies at Kings College, recalls that in a speech to the American National Congress in January 1918, President Wilson announced what became known as the 14 points, in which he stated what would be the basis for lasting peace. His first point stated that “Open covenants of peace, openly arrived at, after which there shall be no private international understandings of any kind but diplomacy shall proceed always frankly and in the public view.” Carvalho writes, “What Wilson is calling for is transparency in diplomacy as a condition for building trust between nations. Secret bilateral treaties greatly, often contradictory, contributed to the beginning stages of World War I. Therefore, transparency, in diplomacy, has become a sine qua non condition for the peaceful settlement of conflicts and stability in relations between nations.” Paulo Nassar, a professor at USP’s School of Communication and Arts, notes that the appeal for a transparent society gained strength with the hyperconnected network society. “Being targeted by all the information that comes to us through all channels and at all the times, we have at first the feeling that we live in a society of transparency and that this is good, because nothing that happens can escape us, that is, to escape our control and our observation,” says the professor, who is also president of the Brazilian Association for Business Communication (Aberje). “However, it doesn’t take long to realize that this excess of transparency is actually leading us to a state of catatonia and consequently paralysis,” he says.

It was in fact what we now call the digital revolution that leveraged the idea of total transparency, giving it the status of widespread near paranoia it exhibits today. It is based in a technology that combines unimaginable ability to store data with the ability to circulate that data by algorithmic commands. This digital transformation eventually created a kind of public surveillance platform in which all social actors (state, government, civil organizations, individual and third parties) are able to watch each other. The effect was to inhibit socially undesirable behavior from any of these actors.

We are now faced with a kind of new Enlightenment (the eighteenth century movement marked by the circulation of ideas) which the Korean-German philosopher Byung-Chul Han labeled the Transparency Society (marked by the hyper circulation of information). It is not for any other reason that the current public debate has become so dominated by the theme of transparency that is prescribed as an infallible moral drug capable of remedying and healing imperfections of the complex societies in which we live. By the way, it is worthwhile to remind ourselves that originally the term transparency comes from the field of science, more specifically, from Optics (I will return to the physical properties of transparency later). “The omnipresent demand for transparency, which has reached the point of fetishism and totalization, goes back to a paradigm shift that cannot be restricted to the realm of politics and economics,” writes Byung-Chul Han in his book Transparency Society (2012).

The messengers of the “power of transparency,” which is undeniably a seductive belief, have failed to ask to the “human nature” if it authorize us to advocate “transparency” as a healthy model of society. To what extent, they should also ask, does a transparent society contribute to the development of democracy, and to what extent does it erode its institutions and the principle of freedom?

In responding to these questions we should consider that the “transparency society” is more of a dystopia that must be questioned than a utopia that must be cultivated.

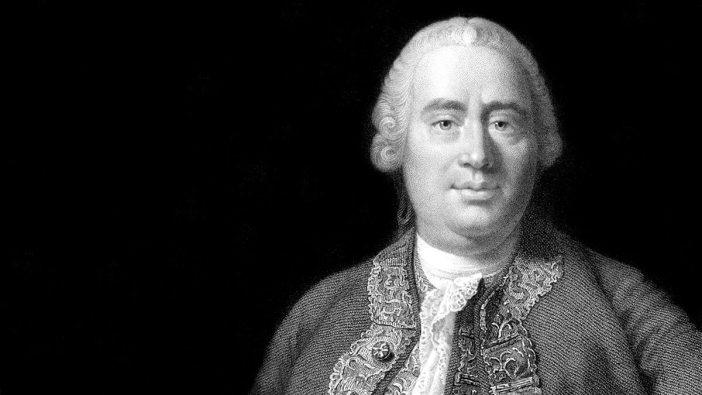

I would like to point out that my arguments against the idea of ‘transparency’ as a panacea for the solution of humanity’s great moral and ethical problems are anchored in a certain branch of philosophy – Empiricism, which considers that moral principles are derived less from reason than from feelings and passions. For this philosophical current, morality is based on what one feels rather than what one thinks. For empiricists, by the way, one’s thoughts ultimately stem from feelings and passions. Thus, in our acting in practical life, we are guided more by our five senses, including taste, which is almost a sixth sense, than by the supposedly clear, autonomous and undoubted light of reason. It is within this context that David Hume wrote in his Treatise on Human Nature (1739), “Reason is, and ought only to be the slave of the passions, and can never pretend to any other office than to serve and obey them.” In this monumental work – in which Hume establishes his theory of knowledge based on perceptions (impressions and ideas) and investigates what motivates our (moral) actions – the notions of “sincerity” and “transparency” (both terms not described directly by the skeptical philosopher) occupy only a secondary role among the virtues that define the sociability of man.

Before considering human nature itself, let us consider nature in general. Now, if we take the word transparency in its most literal sense, we see that it belongs first to the field of physics. It is related to the study of bodies. In a recent article on transparency in the public sector, professors Wilson Gomes, Paula Karini Amorim and Maria Paula Almada note that “transparency is not spoken of in terms of the body that allows the integral gaze of others, but of the body that does not prevent the gaze from passing through it and glimpse other bodies that, if opaque, would hide. ” In fact, the natural condition of bodies is opacity: bodies normally prevent an observer in front of them from seeing the other bodies behind them.“The exception,” according to the three professors, “is transparent bodies, which do not block the passage of the gaze, but, and this is important, they do function as filters. They allow you to see through it, but this view, of course, is limited. The transparent body is diaphanous, that is, it lets in the light, but it is still a body. The body that is the focus of the gaze is literally not transparent, but generally opaque. On the other hand, what is transparent is not the body that one sees, but the body through which one can see another body. ”

That is, to properly navigate the elementary laws of physics, one must be willing to deal with a certain dialectical game between transparency and opacity. This game becomes even more insidious and fascinating when we think about the issue of transparency in the field of animal nature. “The art of deception – the organism’s use of morphological traits and behavior patterns that can evade and circumvent the attack and defense systems of other living things – is a significant part of the survival and reproduction arsenal in the natural world,” says Eduardo Giannetti, in his Self-Deception (1997), a book in which he points to a certain amount of lies, illusion and opacity as inexorable prerogatives that make personal and public life viable.

If in physics and biology, transparency and opacity are somewhat interdependent, in the realm of Freedom, in which ethics is found, this condition is no different: opacity, rather than total transparency is fundamental for a viable life in society. It is part of human nature, notes the rationalist Kant in his Anthropology from a Pragmatic Point of View (1798), that there is a natural resistance to showing ourselves wholly to others and to ourselves. “The human being who realizes that he is being watched and is being examined will look embarrassed and cannot show himself as he is or pretends to be or as he wants to be perceived,” writes Kant. “Even when he only wants to investigate himself, he finds himself in a critical situation, especially when he is afflicted with a condition, a state that usually allows no pretense, namely, when his state is in action, he is not observed, and when one observes, the action is at rest,” adds the German philosopher. For Kant, this sense of hiding in front of the observer and himself is the great obstacle that the anthropologist must overcome in order to minimally see his object of study (man) if he wants to generate any knowledge about him. Now, it can already be seen here that it is precisely opacity (that which we do not see or see clearly) that is the source of knowledge. Therefore, in a totally transparent world, knowledge would already be at risk because it would be notoriously dispensable.

In the history of philosophy there are those who thought that humanity, in its early days, lived in a kind of society of “total transparency”. And the result, as described by Thomas Hobbes in his Leviathan (1651), was the war of all against all. In this state of nature, or total state of transparency, there could be no trust between men and what prevailed was brute force. If anyone took the apple I had just picked from the tree, I would “transparently” and resolutely take the necessary fatal response. That is why it was necessary for men to establish a social contract whereby they abandon their natural rights and submit to the yoke of the state. Now, as opposed to the state of war of all against all, where distrust and suspicion prevailed (all were candidates to steal my apple, my property), the implementation of a contract required a clear exercise of trust on the part of man to establish a civil society.

This naturally wild and transparent man described by Hobbes never existed according to David Hume and even Adam Smith, the two major figures of the Scottish Enlightenment. For them, man is naturally sociable and what ensured his sociability is precisely the game of appearance and opacity that takes place within the system of passions and feelings, which forms their psychology and establishes their codes of conduct. Both philosophers conceive man’s sociability and his walk towards civility as the result of conscious and unconscious bargaining and negotiation strategies between individuals who, at first collaborate to help the other attain their interests and, in doing so, they thereby achieve their own interests. Hume and Smith also talk about the “fellow feeling” with is a human feeling through which we also act without any interest. In any case, those social negotiations are governed by faculties, principles, and feelings such as habit, sympathy, taste, imagination, and utility. Human action is mostly determined by the subjective and intersubjective articulation of these principles and passions. Reason, as stated above, does not play a significant role in human actions.

These internal games and gimmicks have very little transparency: not that they are totally invisible but depend largely on belief and trust.

Hume and Smith’s philosophies, from their epistemological formulations to their political-economic developments, point to trust as the great operator of personal ethics, civic ethics, and business ethics. Trust is an operator who guarantees me a more or less fair walk through the uncertainties of natural and moral life. If I need habit and belief to say that the sun will rise tomorrow (since there is no logical truth to assure me of this, according to Hume), I need mutual trust between individuals or institutions to borrow or sign any other contract. It is, therefore, trust that guarantees our conviviality in complex societies. It is trust that enables us to prosper within these societies. Now, the notion of trust, that is, the deeper meaning of the term “trust” presupposes a high degree of opacity. There would be no need for trust if everything were clear, undoubted and transparent.

Of course, there is no argument here against compliance systems (being transparently in compliance with internal and external policies, laws and standards); or against blockchain technology (technology that also goes by the name of “trust protocol” and which is notable for distributing data and records in a network); or against using big data as a substitute for traditional lobbying to influence public policy and change laws. Nor is it argued against “a world in which governments, businesses, civil society and people’s lives are free of corruption” (statements from Non-Governmental Organizations concerning Transparency). Nor is it argued against the publicity of contracts and agreements between the nations of which President Wilson spoke, and to an even lesser extent an argument in favor of Fake news or Deep fakes or the post-truth (the relative truth of each) and against the truth in its journalistic sense. Equally, I am not arguing here against sincerity, although this is not a virtue that deserves much prominence in Hume’s and Smith’s long catalog of vices and virtues, which instead suggest that a certain amount of hypocrisy contributes to good social arrangement.

The argument against transparency that I have sought to develop and uphold here is, in essence, an invitation to a better critical appreciation of the impositions, determinations, ways, vices, virtues and limits of human nature, as thought by Hume in his monumental effort, anchored in and only in experience, to establish a “science of man” and from this the understanding of all the sciences. The poet T.S. Eliot warned that humanity was not made to endure so much reality. The excess of reality Eliot speaks of is, to some extent, one of the effects of the so-called transparency society. And the American poet does nothing more than warn of the fraying of the natural limit that nature has imposed on our five senses. It is easy to imagine how it is brutal for our physical and mental health that nature had not placed limits on our ability to hear, speak, see, smell and grope. The very notion of love and eroticism would be threatened, since transparency could lead us to an unfailing state of pornography, and here that metaphor of Tapscott and Ticoll’s nakedness no longer seems so funny. “Clearly the human soul requires realms where it can be at home without the gaze of the Other,” says Byung-Chul Han. “It claims a certain impermeability. Total illumination would scorch it and cause a particular kind of spiritual burnout,” he suggests.

If for the individual the excess of transparency leads to this burnout of which the Korean philosopher speaks of, then for society the weakening of the virtuous sense of trust is the greatest loss. Trust is the mainstay of liberal democracies, it is the underpinning of the marketplace. What drives the economy if not the virtue of trust and when converted into expectations, determines prosperity or misery “Trust is only possible in a state between knowing and not knowing. Trust means establishing a positive relationship with the Other, even in ignorance. It makes actions possible despite one’s lack of knowledge. If I know everything in advance, there is no need for trust. Transparency is a state in which all not-knowing is eliminated. Where transparency prevails, no room for trust exists. Instead of affirming that “transparency creates trust,” one should instead say, “transparency dismantles trust.” writes the Korean philosopher.

Reflecting on the virtues and vices of transparency is undoubtedly an imperative for today where everything can be stripped down, but where this “stripped down” can easily be trivialized and naturalized. And going back to the field of physics, we must also ask ourselves: what should we value most, the fact that transparent bodies prevent a complete view of what lies behind them, or the fact that they allow one to see through them? In any case, reflection should consider both the effects of “total transparency” on personal ethics as well as on ethics and business. It is necessary to reflect on opacity because without it there is no identity, and therefore no distinction between self and other. In fact, there are not many “devilish” characters in nineteenth century literature precisely because they have the power to see the feelings and thoughts of others.

Reflecting on the limits of the transparency that we can have on ourselves (the much-lauded self-knowledge), Eduardo Giannetti, in his aforementioned Self Deception, recalls that in the Temple of Apollo in Delphi, next to the inscription “Know yourself” is another inscription, which we pay little attention to and which says,” Nothing in excess. “

This “nothing excess” applies to perfection in this unbridled cry for total transparency. When, in his book 21 Lessons for the 21st Century, the historian Yuval Noah Harari, concerned about the professions of the future, raises the question of what we should teach our children. One possible answer is, perhaps we should, in the midst of the age of Artificial Intelligence and the totalizing and dictatorial threat of data, teach them “the science of man,” the ways in which nature operates in the course of our sociability. This would amount to teaching them a little how to navigate toward Enlightenment, and between the opacity of physical bodies and mind. But this path too must take into account the second inscription of the Temple of Apollo in Delphi: nothing in excess.

*Hamilton dos Santos is a journalist, PhD student in Philosophy at USP and Director General of Aberje – Brazilian Association for Business Communication.

COMENTÁRIOS:

Destaques

- Escola Aberje leva comunicadores para Amazônia em expedição imersiva

- Encontro de líderes debate responsabilidade do setor empresarial e papel da comunicação na COP30

- Aberje realiza reunião presencial com Comitês de Estudos Temáticos em São Paulo

- A comunicação é forte em mercados em que as associações são fortes

- Aberje participa do painel de entidades no 19º Congresso da Abraji

ARTIGOS E COLUNAS

Marcos Santos Maratona da vidaMônica Brissac Thought Leadership: marca pessoal x reputação corporativaLetícia Tavares Liderança comunicadora: um tema sempre atualHamilton dos Santos Comunicação é estratégica na economia contemporâneaCarlos Parente Um salto ornamental para mergulhar no pires